Written By

Katherine Kokkonen

College

College of Public Health, Medical and Veterinary Sciences

Publish Date

12 July 2020

Related Study Areas

The causes and solutions of global health care problems

An unwavering focus on the big picture and a desire to make a difference have fuelled an illustrious career for JCU’s Professor Maxine Whittaker. However, awards for her work in the public health arena don’t signal that it is time for her to relax. There’s still work to do and she’s ready to roll up her sleeves.

Maxine Whittaker takes a no-nonsense approach to work — and work, she does.

“It is hard yakka, but it just needs to be done,” she says. “I’ve got the skills and the energy to do something, so I do it. I love helping people find solutions.”

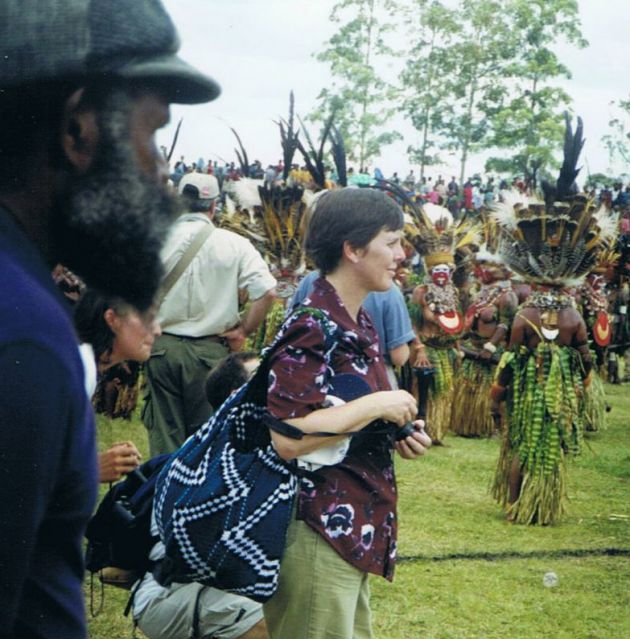

Looking at the big picture causes and solutions of health problems has taken Maxine around the world. She has lived and worked in many countries including Bangladesh, Zambia and Papua New Guinea. Her career spans time in academia, as well as working with the World Health Organisation (WHO), governments, international development partners and NGO organisations.

“I guess you could say I’m not a typical academic,” Maxine says of her rich and varied experience.

Time spent on the ground in communities means that Maxine has witnessed how global politics impacts on the success of local initiatives. When family planning and reproductive health fell out of favour, she saw the harmful effects of ‘trendyism’.

“What I’ve seen is cycles of development,” she says. “What’s in and what’s out of favour affects communities. Trends in donor funding happen and people’s lives, women and children, are affected. We need some consistency and not to give up. Eventually we will win. We did it when we eliminated polio and small pox, so it can be done.”

Determination and focus are traits Maxine started to develop at a young age. During her childhood, her family moved from town to town and she learnt how to rely on herself.

“When you move a lot, you become self-sufficient,” she says. “You learn how to get stuck in and do things as part of the community, wherever you are. I experienced a bit of bullying in school, but I didn’t realise it was happening at the time. Being ambitious and a bit of a nerd in a country high school was hard, but I survived that.”

Maxine not only survived, she thrived. She was the first in her immediate family to go to university, where she studied medicine. While at university she learnt about public health, and her passion for problem-solving found a natural home.

“I knew early in life what I wanted to do and I consider myself very fortunate,” she says.

Her journey in public health has come full circle since the days of learning about the discipline at university. Among her many roles, she is the Dean of the College of Public Health, Medical and Veterinary Sciences at James Cook University. Her tenacity when facing complex issues, such as climate change and eradicating malaria, has earned the respect of colleagues around the world and she was awarded the Royal Australasian College of Physicians International Medal for 2017.

“I’m in there for the long haul and I hope that inspires people to keep trying,” she says. “We need a few people who hang in there and see the bigger picture. I’m very happy to look 20 or 30 years ahead and help bring people along, whether that is through capacity-building, moral support, advocacy or supporting research.”

Universities will play a vital role in the future

Looking to the future, Maxine sees universities as having a vital role to play in solving the world’s wicked problems.

As places that provide opportunities and attract people who have a willingness to make a difference, she says universities can be “the honest brokers” with industries and governments.

“What I like about universities and why universities need to remain supported and part of society is that they can pull together that critical thinking and different perspectives to look at an issue or problem,” she says. “You can’t always do that in industries because that might not make money and you can’t do that in politics because of short-term attitudes. As long as universities do not stay isolated from society, we can help industries, civil society and governments with these issues.”

“As long as universities do not stay isolated from society, we can help industries, civil society and governments with these issues.”

Professor Maxine Whittaker

Having built a career around the world, Maxine is turning her attention to JCU’s backyard and the possibility of working in Indigenous communities. She stresses the importance of only doing such work if she is invited and welcome in the communities.

“When considering poor and vulnerable groups locally and globally, what is required is to be humble, respectful and to think of others,” she says. “We are trying to have a holistic approach with Indigenous communities. We’re looking at health as described by WHO as a state of physical, mental, social and spiritual wellbeing.”

Bringing together people from different fields to work towards a common goal is a skill that comes to the fore in her role as Dean. She leads a College that has disciplines across public health, biomedical science, molecular and cell biology and veterinary science. Fostering collaboration between the disciplines is a way of putting into action her endorsement of the One Health initiative, a movement that recognises that human health, animal health and ecosystem health are inextricably linked.

“For humans to survive it all needs to be cared for,” she says. “It is not about stopping development but there needs to be an understanding about what are the advantages and disadvantages. We need to realise there is some good that comes from the changes and we need to look at how you try to mitigate the negative impacts.”

With so much already achieved, it would be understandable if Maxine thought she had done her part and now wanted to rest. However, the unrelenting Professor casts a critical eye over her work.

“Sometimes I think I’m not doing enough,” she says. “I tell my husband that this is not a profession where I will have an early finish in my career.”

A strong support network enables Maxine to be prolific in her work and she doesn’t discount taking a step back — one day.

“I might slow down a little bit because I do value family life,” she says. “I value having the support of my family and the support of my husband. I have friends scattered around the world. You do find people a bit like yourself. Some of my friends are in their 80s and they haven’t given up.”

Odds are, Maxine Whittaker won’t be giving up any time soon.

Featured researcher

Maxine Whittaker

Professor

Professor Maxine Whittaker is Co-Director of the World Health Organisation’s Collaborating Centre for Vector Borne Diseases and Neglected Tropical Diseases.

Maxine remains active as a teaching and research academic, as well as an adviser to many international organisations. Her major academic foci are One Health, animal and human health systems, and medical anthropology with a keen focus on equity and community ownership and engagement..

She has lived/worked in global health for more than 35 years in many countries in Africa, Asia and Oceania. She has published more than 100 peer reviewed publications, and been awarded and involved in several major national and international competitive, industry and other research grants. In 2017 she was awarded the Royal Australasian College of Physicians International Medal, in recognition of outstanding service in developing countries.