Written By

Hannah Gray

College

College of Science and Engineering

Publish Date

28 January 2022

Related Study Areas

Much more than mangroves

Coastal wetlands are vital to our seascapes, landscapes, marine life, and even our lifestyles and livelihoods. However, our infrastructure and urban development have put these unique ecosystems in jeopardy. Associate Professor Nathan Waltham and Senior Principal Research Scientist at JCU TropWATER, takes us on a journey through the world of the wetlands to discover just how important these environments are.

Nathan says that under the definition of the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance, the wetlands is a habitat that is wet at least for a small part of the year (they can dry out completely), and that extends to about six metres depth along the ocean’s surface. This means that wetlands aren’t just the mangroves, seagrass and floodplains that we might associate them with, but they also include near-shore coral areas with six-metre depth.

The ecosystems that make up the wetlands are incredibly diverse and equally important for the range of services they provide to each other and to the greater environment.

“Many plant and animal species find their home in these coastal wetlands,” Nathan says. “And many species travel great distances to access coastal wetlands. There are migratory birds that fly between China and Australia to access the rich feeding available in our wetlands. These ecosystems are incredibly important for biodiversity as well as holding cultural and social wellbeing values.”

These cultural and social reasons highlight that migratory birds aren’t the only ones who want to enjoy the unique amenities of Australia’s coastal wetlands. Wetlands are beautiful environments. We like to holiday, pass time, build houses, and create entire cities alongside these stunning land and seascapes.

However, our enjoyment and appreciation for this environment hasn’t led to an equal amount of give and take. Our infrastructure, urban development, and recreational and commercial activities have led to drastic changes in the wetlands.

A fish named Jack

The functionality and services of the wetlands are being greatly reduced because of the coastal activity of humans. But this process isn’t always obvious to us, and it can be hard for us to notice the harmful impact that we have on the wetlands because we see it as progress.

“We tend to modify a coastal zone for our own gain,” Nathan says. “In terms of urban development, we like to get as close as we possibly can to the coastal zone. Since industry follows people, this means that industrial development is another big thing that happens along the coast. Add our love for recreational and commercial fishing, and you can start to see that we are changing and even removing the services that the wetlands provide to coastal environments.”

Understanding the connectivity and interdependence of freshwater and seascape wetlands as well as our impact on that relationship requires educating ourselves on the cost of our progress. A prime example of what our love for waterfront property can cost is the Mangrove Jack.

The Mangrove Jack is a wildly popular fish among both recreational and commercial fishers. But apart from being considered “good eating”, as Nathan puts it, the Mangrove Jack is quite fascinating for its life cycle. The juvenile Mangrove Jack lives in freshwater areas such as estuaries and mangrove creeks. Once they reach maturity, they move out of these freshwater areas into offshore reefs, where the juveniles will then migrate from nearshore areas, through estuaries and back into freshwater wetlands to complete their lifecycle.

This is a lot of ground to cover for the Mangrove Jack over their life cycle. If the path between freshwater and reef waters was blocked, their life cycle would also be blocked. As we continue to build highways, bridges, and train lines through wetlands and floodplains, we’re reducing the connectivity that allows these fish to live.

“The interconnectedness of the seascape is necessary for the Mangrove Jack just to exist. If that connectivity is lost, then the species is lost as well.”

Associate Professor Nathan Waltham

The Mangrove Jack isn’t the only highly targeted and iconic species at risk. The Barramundi, a staple in tropical Australian environments, also relies on the connectivity of the seascape.

All Barramundi are born in estuaries as males. As they grow and mature, barramundi transform into females (though some remain as males), and will swim towards freshwater floodplains, which provides a rich source of food. When it rains again, both male and female barramundi move downstream to estuaries and coastal areas to reproduce, which thereby completes their lifecycle.

“When we talk about the functionality and the services of wetlands, it can be hard for people to connect with it,” Nathan says. “But the risk of losing two major fish species is a reality that encourages us all to learn more about the importance of the wetlands and how vital it is that we protect them.”

Sparking a global movement

Lovers of the tropical Mangrove Jack and Barramundi aren’t the only ones to have taken notice of the dangerous reduction of functionality in the wetlands.

Changing hydrology — how water moves across landscapes — as well as a changing climate are stressors of the wetlands’ functionality. The apparent consequences of these stressors have drawn major attention.

“There is now a big interest in restoring the functionality of the wetlands,” Nathan says. “Not just in North Queensland, not just in Australia, but in organisations and businesses around the world. There are now entire networks focusing their efforts on restoring the value and services that wetlands provide. It’s a really exciting opportunity for researchers to work actively in this space.”

Nathan is running a research program that involves working with Indigenous rangers and non-government agencies, such as Nature Conservancy Australia, World Wide Fund For Nature Australia (WWF Australia), and Greening Australia, as well as with NRM groups, government and industry organisations to restore functionality to coastal wetlands.

As for global efforts, the United Nations declared in 2019 that the decade of 2021-2030 would be the decade of ecosystem restoration. Explaining that ecosystem restoration is fundamental to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, the UN says this decade aims to “massively scale up the restoration of degraded and destroyed ecosystems as a proven measure to fight the climate crisis and enhance food security, water supply and biodiversity”.

“There’s been a movement for this kind of change for a few years, so it’s not surprising that we’re seeing it gain traction in recent times,” Nathan says. “There are major philanthropic organisations looking to fund these restoration projects and huge companies looking to invest in this space, especially in reef catchments and the Great Barrier Reef specifically.”

“This global effort is how we’re working to draw a line in the sand and take a stand for protecting, conserving, and restoring our coastal wetlands.”

Associate Professor Nathan Waltham

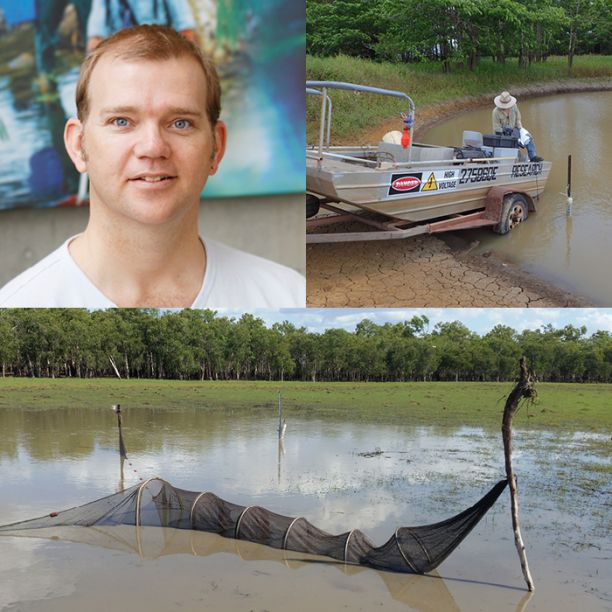

Featured researcher

Dr Nathan Waltham

Principal Research Officer; Senior Research Fellow

Dr Nathan Waltham is a principal research officer and senior research fellow at TropWATER and Deputy Director of the Marine Data Technologies Hub at JCU. He has a keen interest in coastal landscape ecology and processes, particularly urban ecology. He works with a multidisciplinary team of scientists, managers, and policymakers to understand and promote the ecology of coastal and urban landscapes.

Nathan’s research career has focused on using science to provide real world environmental solutions for government, industry, community, cultural and Non-Government Organisations. Nathan is working with government and private companies to channel funding for large scale marine and freshwater wetland restoration – this work is achieving positive water quality, biodiversity and carbon additionality outcomes as a consequence.