College

College of Medicine and Dentistry

Publish Date

10 June 2020

Related Study Areas

How reconciliation supports diverse outcomes

For almost a century, the Kwaio people of the Solomon Islands have been haunted by violent events of the past. Now, an Australian researcher has helped facilitate a peace process to heal old wounds and open the door to new scientific discoveries.

In 1927, a bloody massacre tore apart the island of Malaita in the then British Solomon Island Protectorate.

After a young Kwaio warrior assassinated a high-profile colonial officer, the London Colonial Office asked Australian soldiers and Malaitan police to retaliate. The raids and skirmishes that followed resulted in scores of Kwaio indiscriminately killed. Many more were incarcerated, sacred sites desecrated, artefacts destroyed and cultural taboos violated.

For the Kwaio people, the spirits of those who were killed have lingered for decades, their ire palpable in the remote village communities. Their very presence threatened harm and misfortune at every turn, casting a shadow over Kwaio people’s lives, as well as their dealings with visitors.

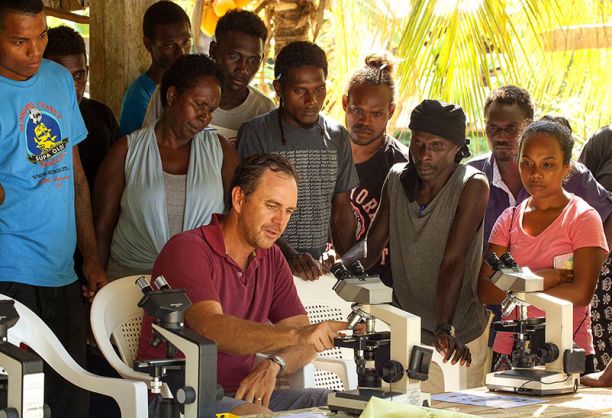

But now, a tremendous weight has been lifted, thanks to an historic reconciliation ceremony in which Associate Professor David MacLaren, a public health researcher at JCU, played a key role. David has been working with the Kwaio community in this remote area of the Solomon Islands for more than two decades. Over the past 12 months, he’s specifically been working with local Kwaio leaders on an international peace process in an effort to reconcile past wrongs.

“This historic event was a constant threat that had never been resolved. So, when outsiders like us were going into these areas, we often felt we were on shaky ground. The spirits of the ancestors who were killed were always there, and angry. Reconciliation would mean we could work there safely and respectfully,” he explains.

“The idea that something needed to be done to reconcile between our peoples has always been there, but this is the first time that there had been a mechanism in place for doing that. It's taken this long working together to build mutual trust and respect, and bringing the right people together to make it happen.”

Death and taxes

In the early 1920s, when the Solomon Islands was still considered a British protectorate, colonial officials began imposing an annual ‘head tax’ on the people of Malaita.

But as the years passed, it became clear that the British protectorate was not interested in providing public services in return for these mandatory payments. This bred resentment among many Kwaio tax payers, and, one day in 1927, when the Australian-born District Officer of Malaita, William R. Bell, arrived to collect the payments, he was assassinated by a young warrior named Basiana.

This act of violence triggered a chain of reprisals that would come to be known as the Malaita massacre. It resulted in the direct killing of scores of Kwaio people and indirect death of hundreds more. While violence was not uncommon at the time – tribal skirmishes had been flaring up for as long as anyone could remember – peace and reconciliation processes were always used to resolve these conflicts.

But the British and Australian officers had little interest in such a process, and without reconciliation, the spirits of the dead remained to haunt the Kwaio people.

“It was unfinished business,” says David.

Having formed a close relationship with the Kwaio over many years, David was asked to get involved.

“Early this year, I got sat down by some of the chiefs and they said, ‘David, we want to move forward, but we need to sort this out. If you get the white guys sorted, we'll get our side sorted, and then we can plan for reconciliation’. It would make our partnership stronger and more respectful. It would make our work easier and safer — for us all.”

David needed to find a representative of the Australian people to participate in the ceremony, and sought out Tim Flannery, an internationally renowned palaeontologist, mammologist, and conservationist, as the perfect candidate.

Not only did Flannery’s former Australian of the Year title earn him the acknowledgement of the Kwaio chiefs as a leader of the Australian people, but he was also happy to trek into the remote Kwaio mountains, having conducted mammal surveys on Malaita some twenty years ago. He has spent much of his career seeking out rare and remarkable species in hard-to-reach Melanesian forests, so understood the task at hand.

“It was a really interesting concept, where those of us in the living world were now very close and didn’t have any personal enmity, but we as leaders had the responsibility to sort out those historic wrongs that our people had done to each other in the past,” says David.

The reconciliation ceremony was performed in July at a sacred site in central Malaita. A Kwaio priest called on the wild ancestral spirits by name to possess a young piglet, which was then let free into the surrounding rainforest.

“Because it was so small, it would inevitably die in the rainforest, and symbolically, the angst and the anger of all those spirits that had been indiscriminately killed would die along with it,” says David.

Once released, the wild spirits were transformed into benevolent domestic spirits, which are now believed to linger in the village to protect, rather than punish, the local community.

The second day of the ceremony involved David, Tim and another Australian scientist Dr Tyrone Lavery gifting three more pigs. In exchange, traditional Kwaio shell money was given to the three Australians to pass on to the Australian people, as compensation for the Australians who were killed in the massacre. The gift is now housed in the archives of the Australian Museum in Sydney.

“It was a great opportunity – a chance to help resolve something that we all knew was a real burden for the community. "

Associate Professor David MacLaren, JCU

The process was not just about healing old wounds for the Kwaio people; it’s opened up the possibility for more researchers like David, Tim and Tyrone to collaborate with these communities into the future.

And for David, the impact has been profound.

“It’s a story about history, about relationships, about righting wrongs. It's a story about people wanting to work together, and about this really beautiful balance between traditional ways and scientific research, and how they can co-exist,” he says.

“Traditional knowledge is really important to understanding the ecology and the conservation of many of these plants and animals. And now our Kwaio friends want to engage with researchers who can do DNA analysis to confirm where the unique species are on the island.”

A team of bird experts from the Australian Museum have subsequently visited the region and are working with the Kwainaa’isi Cultural Centre and community conservation groups to document the endemic birds of Kwaio. Flannery and the mammal team from the Australian Museum also continue their partnerships in Kwaio in pursuit of a native rat the size of a possum, a unique species of flying fox, and many other unique species in the area.

Teams of frog and reptile scientists are also planning to link with community conservation groups next year to document native species and assist the Kwaio people in their conservation efforts.

“What’s cool is that the land is customarily owned. There’s a whole series of small, tribal-level conservation areas, where people have absolute control over their own land,” David explains. This isn’t an international organisation, it's not government, it's not a university imposing anything. It's those guys saying, ‘Let's put this bit of land away, and let's not cut down any trees, or let's not hunt any animals in here’.

"It's a totally different model, and the conservation outcomes are going to be fantastic.”

Public health initiatives

Beyond the conservation work that will come out of the peace process, the opportunities for David to continue to support local public health initiatives in the area are enormous.

What that means for a disease like tuberculosis (TB), which remains highly endemic in the Solomon Islands, is not just looking at how you can diagnose and treat it, but also understanding, from a local perspective, how people believe TB is transmitted in the first place.

“It might be sorcery, or it might be something to do with the spirits. Therefore, the interaction with Western biomedicine is really kind of profound,” says David.

“If you believe that a sickness is caused by a germ and this tablet will kill the germ, then you might be committed to taking that tablet every day for the next six months. But if you believe that your cough is because of spirit possession or sorcery, then taking a tablet for six months is a bit of a crazy thing to do, from that kind of logic.

“Understanding that interplay of what people believe, and how health services are able to engage with the community — that’s the area I work in.”

David is keen to point out that he’s not there to impose Western treatments in cases where traditional medicine can be just as effective, such as for minor infections, diarrhoea, or head lice.

David is hopeful the goodwill established by the reconciliation process will support efforts at a local research hub, the Kwainaa'isi Cultural Centre, to engage local leaders in combined health and conservation initiatives.

“We can make sure that when we have conservation meetings, we say, ‘Hey, take your whole family, and we can get a medical team in there to do your immunisation.’ So, the next time there's a measles outbreak, the kids in the area won't die, because they have been immunised,” he says.

Now, as the Kwaio people work towards completing a similar reconciliation process with the descendants of the Malaitan police who were involved in the massacre, David is optimistic about the future for the region.

With the weight of ancestral torment lifted, and respectful partnerships strengthened, this is just the beginning of a new era of collaborations and discovery.

“It's a story of redemption and coming together. It’s an acknowledgement of the past, while also looking to the future,” says David.

“While the consequences of colonisation are enduring, there are innovative ways of reconciling some of painful parts of history — to let us move on.”

Featured researcher

Associate Professor David MacLaren

Principal Research Fellow

David is a public health researcher with two decades of experience in addressing community health issues in remote areas of the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea. His work focuses on understanding the complex connections between biomedicine, health service provision, and socio-cultural understandings of health.

In PNG, David is collaborating with partners to investigate methods of HIV prevention and faith-based responses to HIV. David also works in partnership with the Australian Museum and the Kwainaa’isi Cultural Centre in the Solomon Islands on a range of culture and conservation projects.