Media Releases

Tweeting Disaster

Most of us spend part of our days ‘Tweeting’ or ‘Facebooking’ – there’s no getting away from the pull of social networking sites. But new research shows that sites such as Twitter and Facebook could be crucial in sharing information during large-scale emergencies.

A newly developed disaster management portal, developed by James Cook University researchers Jess Faber, Trina Myers and Ian Atkinson, along with colleagues from Griffith University in Brisbane, uses Twitter to gather up-to-date information.

Following a disaster such as a fire or flood, essential services such as electricity and phone lines can fail - just at the moment when the need for up-to-date information is crucial for disaster recovery and planning - and also for those awaiting news of loved-ones. Research shows that collective knowledge from social networking sites can be more beneficial than mainstream media in the initial stages of such a disaster event.

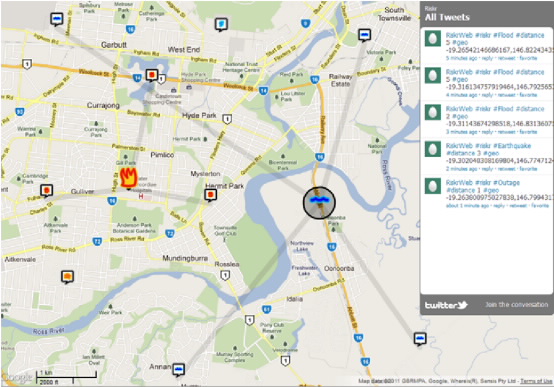

The researchers developed the Riskr Project to investigate whether large social networking sites, such as Twitter or Facebook, could be used to feed information into a central disaster portal. Ideas from current disaster portals were incorporated into Riskr, along with features that take advantage of the social network Twitter.

The portal consisted of a web server, a map interface and a newsfeed. The Riskr portal was tested on campus at JCU – users were given the mobile web service to report a hypothetical fire at the library. The majority of users reported that the portal was easy to use and understand, and more than 70% of users could estimate the correct location of the disaster.

Dr Ian Atkinson said portals like Riskr could work to help organise emergency services. “The system was intended to be used as a conduit from the public to emergency services. As more data from public networking is entered, the system builds a more accurate picture of an event that can be used to better plan and respond,” he said.

Dr Trina Myers said: “This form of accessible collective knowledge could also be extremely valuable source of information to the public at the time of an event, such as a power line down or flood water.”

The primary advantage of a portal like Riskr over conventional media sharing is the rapidity with which accurate information can be disseminated.

Although Riskr itself is not planned for further development, the ideas developed from it could be used in many situations and the research into using prescriptive syntax over social networks will be used in future disaster portals.

“The idea is to ‘harness the crowd’ in a way that can offer and aggregate real-time information,” Dr Myers said. “Besides disaster management, we are also investigating whether similar systems can be used in citizen science, business and marketing, and tourism in the Great Barrier Reef.”

Contact: Dr Trina Myers

P: (07) 4781 6908