Striving for sustainability through biosecurity

In 2024, the International Day of Women and Girls in Science (11 February) celebrates Women & Girls in Science Leadership: A New Era for Sustainability. Discover how JCU Alumni Dr Pauline Lenancker’s research on the biological processes of invasive ants and her work in biosecurity responses to ant infestations helps improve Australia’s environmental sustainability.

When researching exotic parrots in Paris for her Master’s thesis, Pauline found that even though parrots don’t really belong in France, they weren’t seen as a genuine threat. So she decided to up the ante and go to Australia. “Australia is the country that is the best in the world in terms of managing biological invasions and at the forefront of biosecurity research, especially in regard to invasive ants,” Pauline says.

After completing a student project at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) in Darwin and in Canberra, she was granted a scholarship to work on a PhD research project in this field. “I came to JCU to work with Professor Lori Lach,” Pauline says. “Lori is an amazing researcher who has done extensive research on invasive ants, and she became my Primary Advisor. She is also a great mentor, and she made me a better researcher.”

In her PhD thesis, Biological processes influencing the success of invasive ants, Pauline decided to focus on tropical fire ants and yellow crazy ants. She says that tropical fire ants and yellow crazy ants are not only a major problem in Australia. “They are some of the world's worst invasive species,” Pauline says.

The impacts of these colonies can be far reaching, as they are known to drive away all animals that live in the vicinity of their nest. “These ants take over the whole ecosystem, and they attack anything that is ground dwelling,” Pauline says.

“Yellow crazy ants, for instance, build massive colonies. They spray acid in other animals’ eyes, which can be a bit nasty. They even attack pets, nesting birds or farm animals, as they don't have much fear of big animals.”

At the same time, yellow crazy ants also have the potential to wipe out crops such as sugar cane or fruit trees, as these ants are known to protect moulds and other pests that produce food for them.

Pauline says that yellow crazy ants can be found as far north as Arnhem Land, including in Cairns, and as far south as northern New South Wales. “We have had an infestation in Lismore, in New South Wales,” she says. “A biosecurity response was undertaken to eradicate the ants. They were last seen in October 2021, but we are still doing regular checks to make sure they have all been eradicated.”

Understanding the environment

For her PhD research, Pauline had to breed her own tropical fire ant colonies, while making sure that the ants could not escape from their controlled environment. “I looked after dozens of newly mated queens, and they were laying eggs and looking after the first generation of workers,” she says. “I found that after the first workers of the colony have hatched, the queen no longer needs to look after the brood.”

Pauline says that when invasive ants move to a new region, they become isolated from other colonies in their native range. “They go through what we call a ‘genetic bottleneck’, which means that genetic defects can develop. For instance, I would see that some of a queen’s offspring would be very fat larvae. I called them the ‘fat babies’,” she says. “They were not meant to have such big larvae at this early stage in the life of the colony.”

Pauline also noticed that, after a while, some queens would simply eat all larvae that were too big. “Witnessing cannibalism in tropical fire ant colonies was quite surprising and unexpected,” she says. These research findings were also published in Nature, one of the world’s premier science journals.

Exploring the blueprints of behaviour

One of the skills Pauline learned during her PhD research was to interpret DNA data collected from invasive ants. She says that this skill is very helpful in her current role as a Project Officer for Invasive Invertebrate Biosecurity at the NSW Department of Primary Industries.

“I can be that conduit with people working in different areas. First, I read the DNA reports, and then I can explain what it means to other stakeholders. So it's a very useful skill in general,” she says. “For example. I can explain how ant colonies are related to each other by looking at their genetic relatedness.”

Pauline is also one of the first contacts when there is a response to invasive ants. Given that she has examined the behaviour of invasive ants for almost ten years, she is one of the top specialists in responding to ant infestations in Australia.

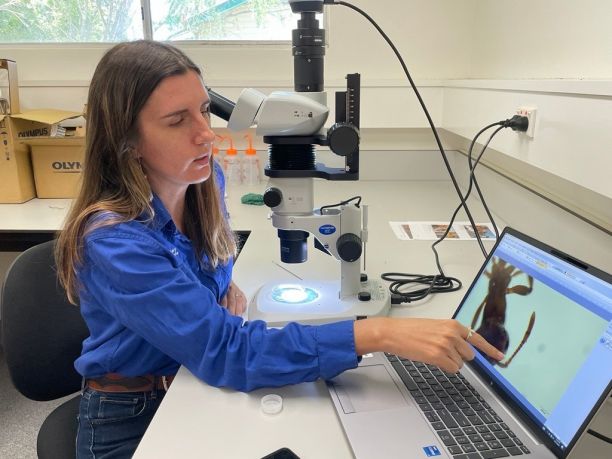

“I look at suspect ant reports for fire ants in New South Wales. If I think the report is suspect, I will organise for someone to obtain a sample and take it to one of our microscopes,” Pauline says. “These microscopes can be accessed remotely by other specialist entomologists (ant experts) in New South Wales and Queensland.

“If the ant is confirmed to be a biosecurity risk, such as a red imported fire ant, I provide expertise in the biosecurity response for everything from ecology to biology,” she says. “But I also conduct risk assessments and work in the policy space.”

Leading sustainability through a career of curiosity

In light of the upcoming International Day of Women and Girls in Science on February 11, Pauline notes the importance of encouraging women and girls to explore and innovate within the world around them. “Women and girls should consider a career in science because it's just such a rewarding career. It's great to develop that sense of curiosity in everyone,” she says.

For Pauline, having an assortment of mindsets and viewpoints in science is key to its progress. “We should encourage all little girls and little boys to do science. You always need new ideas,” she says. She believes that science is strengthened by diversity, and that encouraging women and girls from all walks of life to pursue science can lead to greater innovation.

“Bringing international researchers to Australia, for instance, is great. They'll have different expertise and different mindsets because they've had a different upbringing and research experience. The same goes for women and men working together,” she says. “It's good to have that diversity of people working together because that makes science stronger. It makes science better because you get more ideas and solutions coming from people with different backgrounds.”

Pauline’s research and international perspective has made a significant contribution to the ways in which Australia manages its invasive ants. Her work is just one example of how women in science are leading scientific and sustainability progress.

What to do when spotting invasive ants

Yellow crazy ants have been found in Queensland, New South Wales and the Northern Territory already and red imported fire ants in Southeast Queensland and New South Wales. Pauline suggests contacting the relevant state department to report any suspicious findings.