Written By

Katherine Kokkonen

College

College of Science and Engineering

Publish Date

16 April 2020

Related Study Areas

Balancing development and conservation

Pristine beaches and lush mangroves create coastal oases for a range of flora and fauna. But sooner or later humans discover these havens and development can follow. What if instead of being seen as opposing forces, development and conservation could be balanced?

Palms swaying in the breeze, the ocean lapping on the shore and warm light enriching the greenery — no doubt about it, the tropics is paradise. Why wouldn’t you want to do business here and call it your home?

But where people go, development occurs. Hard engineering structures occupy about 10 per cent of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park’s coastline.

“Is that too much or is there room for more development?” JCU’s Dr Nathan Waltham asks. “We’re not sure yet, but what we do know is that development is happening.”

If development is going to happen regardless, could shoreline development and urban areas be engineered in a way that mitigates potential negative impacts?

Nathan is trying to find that balance between urban development and environmental protection. He is focused on how we are changing the coastal seascape from a natural network of mangroves and seagrass to coastal and agricultural development.

“If development is not planned or managed then you have a reduction in the overall extent of natural coastal habitat,” he says. “You have a disconnect if you build urban development that impacts on wetlands and estuaries, the places we work and play. But there are other consequences, like a decline in water quality and changes to the amount of habitat available for animals such as fish – these are the very challenges facing managers.”

Protecting habitats around the world

To protect habitats, the solution is to go green.

This means building structures that have places for animals, such as barnacles and oysters, to live. It also means installing water treatment into urban streetscapes to polish rainfall runoff before reaching local rivers and creeks.

“We are looking at how green engineering can improve the hard infrastructure that is coming in and how it can directly improve water quality,” Nathan says.

“Green engineering looks at hard engineering and gives it soft features and characteristics that provide habitats with things to attach to and grow.”

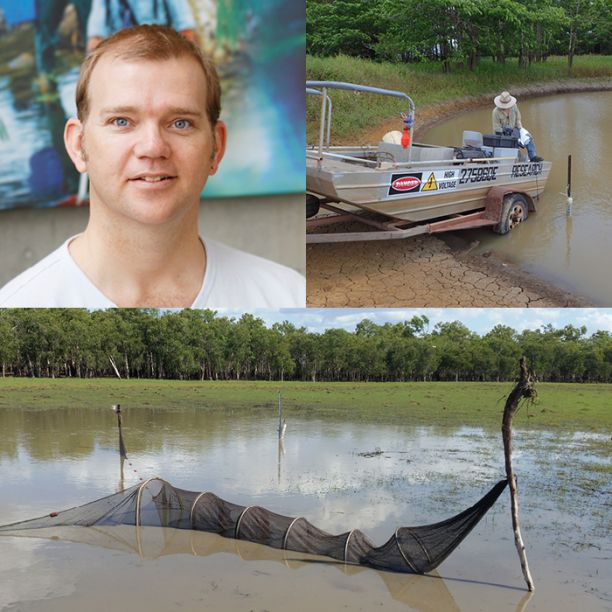

Dr Nathan Waltham

The green engineering philosophy is starting to gain traction. Project demonstration sites overseas are happening. Locally, the Cassowary Coast Regional Council is investigating green engineering solutions for a seawall renewal program.

“They had heard of the concept and the ideas and it was good timing for it to be considered as part of the foreshore redevelopment project,” Nathan says.

Whether projects are at a local level or on a grander scale, Nathan stresses the importance of engaging with stakeholders. Ideally, representatives from government, business, conservation groups and the community would come together before any building occurs.

“We need all the stakeholders at the table and it is important that they are at the table early in the design phase,” he says. “We are starting with smaller projects and there are sites up and running. We hope to show the success of these projects and then take those learnings elsewhere.”

Green engineering has the potential to preserve habitats and improve water quality in large cities, however retrofitting solutions brings with it a range of challenges. Nathan is coordinating with colleagues in Singapore, and looking at projects in the United States and the UK that explore these urban ecology challenges.

“The challenge of megacities in the tropics is that they already have heavily modified coastlines and port facilities,” Nathan says. “We have to look at how you go back and modify that infrastructure and what cost is involved. These are places where we’ve got huge changes in population in coastal areas and we have to realise there will be more expansion of industry and urban development, and make sure we can protect water quality through smart water treatment design technology.”

With green engineering making its way into the limelight, Nathan is hopeful that it will continue to flourish locally and make a difference for both coastal communities and the environment.

“My goal is for green engineering to grow so we can tackle these issues in expanding megacities in the tropics, and tackle coastal water quality challenges,” Nathan says. “There is always more that can be done. It’s through working with other researchers and stakeholders that we can start to progressively achieve success in the space of coastal development.”

Featured researcher

Dr Nathan Waltham

Principal Research Officer; Senior Research Fellow

Dr Nathan Waltham is a principal research officer and senior research fellow at TropWATER and Deputy Director of the Marine Data Technologies Hub at JCU. He has a keen interest in coastal landscape ecology and processes, particularly urban ecology. He works with a multidisciplinary team of scientists, managers, and policymakers to understand and promote the ecology of coastal and urban landscapes.

Nathan’s research career has focused on using science to provide real world environmental solutions for government, industry, community, cultural and Non-Government Organisations. Nathan is working with government and private companies to channel funding for large scale marine and freshwater wetland restoration – this work is achieving positive water quality, biodiversity and carbon additionality outcomes as a consequence.