Written By

Mykala Wright

College

College of Public Health, Medical and Veterinary Sciences

Publish Date

11 December 2023

Related Study Areas

What is veterinary epidemiology?

JCU Professor Bruce Gummow has spent a lifetime forging a unique path in the veterinary sciences. His journey has led to ground-breaking achievements in animal disease prevention, control and eradication across almost every continent.

Animal diseases not only impact the health and productivity of animal populations, but they often affect the human communities associated with them. In fact, it’s estimated that 60 per cent of infectious disease outbreaks in humans have originated in animals, including COVID-19. Veterinary epidemiology plays a crucial role in understanding, controlling and preventing these outbreaks.

“Most veterinarians treat individual animals, but veterinary epidemiologists investigate diseases in populations of animals. My job is to investigate what causes outbreaks of disease and to figure out where it might have come from and how it can be prevented,” Bruce says. “I get to work all over the world with many different types of animal populations, which have ranged from molluscs in aquaculture farms to elephants in game reserves. This makes my job very diverse and is one of the reasons I love being an epidemiologist.”

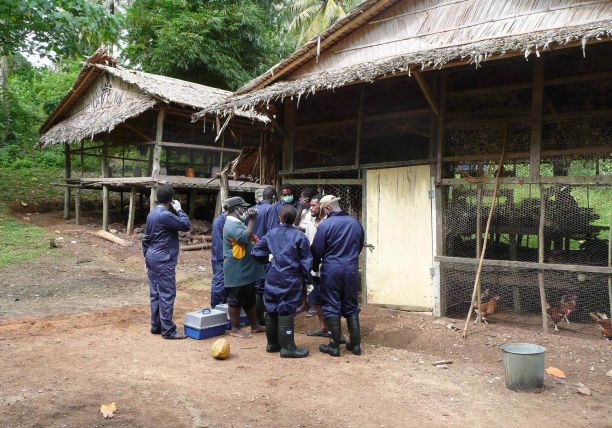

Much of Bruce’s career has focused on building veterinary epidemiology capacity in developing countries throughout Southern Africa, South East Asia and the Pacific Islands. Disease outbreaks in these locations are especially devastating because livestock are an integral part of the culture of these communities and often their only source of income.

“In countries without a solid social security system, village chickens and pigs act as a source of income and social security for many unemployed people. Since these communities rely on the animals for their income, if they die, people literally starve,” he says.

“Effective animal disease prevention and control relies on a solid understanding of the epidemiology of diseases. Epidemiologists are trained to figure out how diseases spread and how to prevent and control them. My goal is to ensure that countries in the Tropics have people with the epidemiology skills to improve animal disease surveillance and support rapid detection and prevention measures.”

A Lifetime Achievement

Bruce was first introduced to epidemiology while working as a veterinarian in the South African Medical Service. At the time, epidemiology wasn’t taught in the veterinary science curriculum.

“The medical services had me working on a project on rabies as part of a One Medicine team that included medical doctors. While I was doing that, they enrolled me in an online epidemiology course with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),” Bruce says. “Back then, veterinarians from Southern Africa had to go all the way to Europe or America to get any training in veterinary epidemiology.”

After completing his national service, Bruce worked off a government bursary as a research veterinarian. He retained his interest in epidemiology and began applying his epidemiology training as a government veterinarian. Five years later, he was approached by the Faculty of Veterinary Science at the University of Pretoria (UP) in South Africa and asked to set up the veterinary epidemiology curriculum.

“I drew on what was being offered in the USA at the time and gradually built the curriculum up from undergraduate level to PhD level. I was one of the first in the world to teach epidemiology as an applied subject in the final years of veterinary science. However, there were still thousands of veterinarians in Southern Africa that had never been taught epidemiology and it would take generations of veterinary students to build up capacity through the new curriculum,” Bruce says.

“I decided the only way to solve this problem was to create a regional epidemiology organisation that could be used to bring likeminded veterinarians together and provide a forum for training and collaboration.”

So, Bruce founded the Southern African Society for Veterinary Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine (SASVEPM) in 2000. With the Society, he brought experts from all over the globe to South Africa to hold workshops and provide epidemiology training to regional veterinarians. Since then, it has grown into one of the largest regional epidemiology societies in the world and continues to build capacity among veterinarians.

Now, 23 years later, Bruce’s contribution to veterinary epidemiology and preventive veterinary medicine over the past two decades was recently recognised when he received a Lifetime Achievement Award from SASVEPM.

“Through the Society and my own personal teaching of veterinary epidemiology, I have been able to achieve my vision for building veterinary capacity in resource-poor countries that is sustainable, and sees veterinarians stay in the region to have a continuing impact on disease control,” he says.

“To be recognised with this award as achieving something positive by peers and colleagues is very rewarding for me.”

Building capacity across continents

Bruce’s contribution extends much further than Africa. He has also established collaborative veterinary networks in Australia and continues to facilitate epidemiology workforce development in Southeast Asian and Pacific Island countries.

“I have built up disease surveillance networks across multiple continents and I’m continuing my vision of developing veterinary epidemiology capacity in vulnerable communities through postgraduate training and research projects,” Bruce says. “Many of my Master’s and PhD students have gone on to senior veterinary and animal health positions and some of them are now Chief Veterinary Officers in their countries; one of them is even a Permanent Secretary for Agriculture. They are now able to implement policies that can have a major impact on disease prevention, control and eradication in tropical parts of the world where many diseases emerge. I find this very satisfying.”

Recently, Bruce has been supervising PhD students who are investigating how village farmers trade and move their animals.

“By understanding this movement of animals and animal products in developing countries, we can focus limited resources and animal health capacity in places where the most trade is occurring. These hotspots are where diseases are most likely to be contracted by healthy animals and then transmitted on to other places,” he says. “We have also been looking at ways to incentivise village farmers to report disease when they see it, as they are our front-line of disease detection.”

This is called syndromic surveillance. Different cultures value animals differently and in some cultures, people don’t always see the benefit of reporting animal diseases.

“Understanding what’s important to these cultures will help us create a better reporting system for early detection of disease outbreaks. This has got me working with anthropologists and sociologists, which adds another fascinating dimension to my work,” Bruce says. “Much of my career has focused on building capacity in veterinary epidemiology in tropical regions of the world where many diseases emerge. This has been furthered by student alumni who have exponentially increased the impact I’ve had during the lifetime of my career in preventing, controlling and eradicating diseases in the Tropics.”