Written By

Mykala Wright

College

College of Arts, Society and Education

Publish Date

10 November 2022

Related Study Areas

Craving convenience

The natural environment plays an important role in the overall well-being of humanity. Not only does it provide us with resources essential to our survival, but being in nature has been proven to positively impact our physical, social and psychological health. Despite these benefits, we are becoming more and more disconnected from natural spaces and processes.

JCU PhD Candidate Rachael Walshe is exploring how this disconnect manifests itself in our relationship with food.

“I’m looking at gardens in school curriculum and how they have the capacity to improve the human-nature nexus,” Rachael says. “For the most part, children don’t really recognise that food is natural, or that they themselves are a part of nature. I think that if we can bring gardens into schools and have children interacting with food and nature on a daily basis, it encourages food system awareness and gets them thinking about food resilience early on.”

In our fast-paced world, consumers crave convenience. We are spoilt for choice at the supermarket, where we have access to an abundance of fresh produce all year round, grown all over the globe. But we tend to take it for granted that we can eat avocado on toast every day, and our lifestyle of convenience has left us unfamiliar with what food grows where and when.

“There is a really big disconnect in what goes on in our food system. Here in Far North Queensland, food is grown and then shipped to Brisbane before it is shipped back to be put in the supermarket; I don’t understand how that is sustainable,” Rachael says.

“And then we’re purchasing fruit and veg that goes off within a couple of days. A lot of people don’t have an understanding of what is actually in season where they live. When it comes to feeding people, local is best because if the transport systems in Australia or worldwide fail, the food system starts to fail. All of us in urban environments are food vulnerable because if we don’t have access to the produce, we also don’t have the skills or the knowledge to grow it ourselves.”

You are what you eat

Rachael’s research investigates the effect of environmental generational amnesia on children’s perception of food and nature.

Environmental generational amnesia is the idea that each generation in its youth perceives the condition of the environment into which it is born — no matter how developed or degraded — as normal, forgetting the natural world as it once was.

“Basically, children are regressing from the natural realm and thinking that nature is just out there, and not something that is a part of their everyday world. The more we move into urban living and dwelling and the less contact time we have with nature as kids, the less we consider ourselves a part of it,” Rachael says.

It has been suggested that more frequent interactions with nature can enhance children’s connection to and knowledge of nature and natural processes. Rachael puts this theory to the test by comparing how environmental generational amnesia manifests in children taught in Montessori and mainstream education systems.

The Montessori method is a self-directed approach to education that sees students learn through activities and play, as opposed to a traditional, teacher-led classroom.

“Montessori is an inquiry-based learning style,” Rachael says.

“It is often overlooked because it’s an alternative form of learning. But children are curious, and it allows them to move around the classroom freely and find their own niche and their own confidence within the school system. Everything is very hands-on; they do with their hands first and then they write about it.

“The school I work with is a state school in Cairns that has a separate fenced-off Montessori section that teaches the national curriculum. The Montessori students spend one day in the garden every single week and for that day all of their lessons are in the garden.”

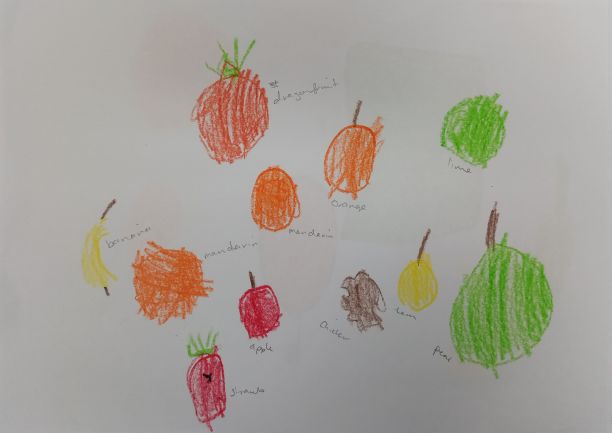

For her research, Rachael interviewed faculty at the school she was working with to get a better understanding of the influence of gardens in schools. Following that, she asked prep and Year 1 students from the Montessori classroom and the traditional classroom to draw what they thought of when they heard the word food.

“I gave them crayons and I gave them 15 minutes to draw, and then at the end I went around and asked them exactly what they drew because sometimes it wasn’t obvious,” she says.

“I chose those year levels because before we’re seven years old, we are our most impressionable. That’s when our fundamental core values are ingrained in us. They’re also age groups that are really underrepresented. I think children need to have more of a voice in research that involves them.”

Let it grow

Rachael’s research found that the students who were in the garden once a week, having regular contact with nature, were more environmentally conscious and had a greater understanding of place-based food.

“Some kids from the standard teaching stream drew natural foods, but most drew processed foods like pizzas, lollies and burgers. I also got a lot of branded foods like McDonalds, Coca-Cola and Skittles,” she says. “The kids in the Montessori class not only drew a greater diversity of fresh fruit and vegetables, but they also drew things that were more relevant and local to Cairns.”

Beyond being beneficial to the students, Rachael’s research revealed that spending time outside and in the garden positively impacted staff as well.

“Teachers are strapped for time. It takes a village to raise a kid and these teachers are very much doing a huge part of that, and they need these spaces, too. I discovered that teachers really benefit from having outdoor contact time; the calming natural environments on school campuses really help their mental wellbeing,” Rachael says.

“Often, school gardening programs are considered beneficial for limited subjects, like home economics. But that’s not the case; gardens in schools are a form of place-orientated education that fit the entire curriculum and they can help children build the bonds they so desperately need with the natural environment.”

PhD Candidate Rachael Walshe

“They’re awesome for teaching children about geography and place. For example, children can grow a plant from their culture and explore what that means to their culture and represent themselves within the school environment in a diverse way. They can do mathematics using plants, like volume, scale and time. And there are so many different terms used in gardening, so gardens help children to begin to think outside of the box with their English skills, too.”

Rachael hopes to see more gardening programs implemented within Australia’s school curriculum in the future.

“I’m creating an evidence-based document that I can take to Queensland Education that demonstrates the benefits of gardens, the barriers to gardens and how they work in the curriculum. I think if we can get kids to consider what grows locally and seasonally within schools, without really enforcing it on them, we are encouraging greater environmental awareness early on in life.”

Want to know more about Rachael’s research? Read about her work in community gardens.

Featured researcher

Rachael Walshe

PhD Candidate

Rachael Walshe is a PhD Candidate in the Doctor of Philosophy (Society and Culture) at James Cook University. She has a Class I Honours in Human Geography and a Bachelor of Environmental Management (Sustainability and Human Geography).

Rachael’s research explores environmental education, food resilience and environmental belonging. Her thesis focuses on the effect of environmental generational amnesia on children’s perceptions of food and nature.