Written By

Bianca de Loryn

College/Division

College of Healthcare Sciences

Publish Date

18 October 2022

Related Study Areas

A special connection: Humans and their pets

Dr Jessica Oliva, Senior Lecturer in Psychology at JCU, tells us how cat and dog owners have weathered the COVID-19 lockdowns in 2020, and how pets coped when their owners could suddenly go out again after the lockdowns eased.

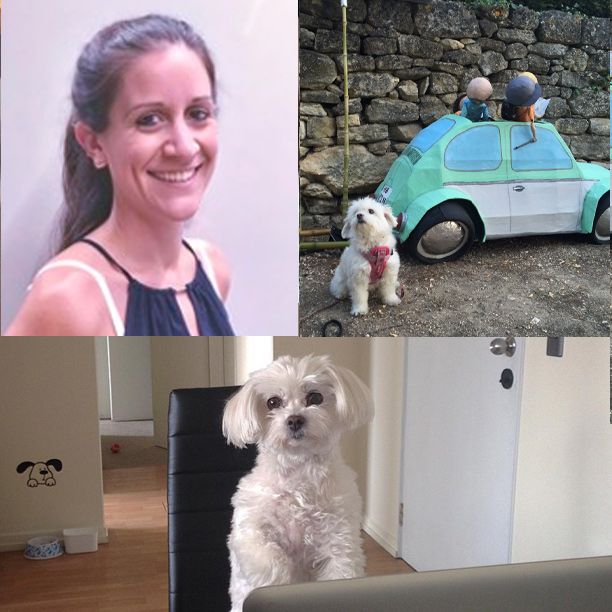

Humans have a history of bonding with their cats and dogs, and so does Dr Jessica Oliva. “After I adopted my dog Bonnie from the shelter, I became interested in human and pet relationships,” she says. Bonnie was a Maltese Terrier that made a real difference in Jessica’s life, so much so that she decided to research the role of oxytocin — the ‘love hormone’ — in human-dog bonding and communication for her PhD thesis .

Fast forward a few years to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when many people suddenly had to stay at home for long periods. “When the lockdowns happened, and people were very disconnected, I thought, ‘well, I wonder what the effect is of people living alone with a pet versus people who live alone without a pet,” Jessica says.

Pet ownership and mindfulness

Jessica is not only a psychology academic, but also a yoga teacher with a personal interest in mindfulness. “Mindfulness means being in the present moment, attending to whatever is happening in the moment,” Jessica says. “I know from my own experiences with my dog that pets can have this ability to really bring you into the present moment. It's hard to be distracted when you're interacting with your dog.”

This is why Jessica and her colleague Kim Louise Johnston researched pet ownership and mindfulness during the pandemic. “Social media was a godsend for us, and we were able to recruit almost four hundred people from around Australia,” Jessica says. 111 of those who filled in the online survey were dog owners, 103 were cat owners, and 170 people lived alone without a pet.

‘Cat people’ are different

When it comes to pet ownership and mindfulness, Oliva and Johnston found that having a pet didn’t necessarily make people more mindful. Instead, they noticed that cat owners were even less mindful than non-owners. That wasn’t a big surprise for Oliva, though. “There was a research group in England that was looking at people who were self-professed ‘dog people’ or ‘cat people’ or both.

They found that cat people scored higher on neuroticism. But they also scored higher in regard to ‘openness to experiences’, which I think is quite an interesting finding,” she says.

Unlike cat owners, dog owners were well protected against loneliness in the early pandemic. “Dogs were providing an opportunity for owners to go outside and exercise. That itself afforded opportunities to interact with other people doing the same thing,” Oliva says. “Then we thought: the dog is acting as a catalyst by helping people have these social interactions.”

The pet perspective

The researchers also wanted to look at the lockdown situation from a pet perspective. So, Jessica and her colleague asked pet owners how their cats and dogs behaved during the lockdowns. “Most pets were happy to have their owners home all the time,” Jessica says.

“But cats showed a greater range of emotional or behaviour changes, with some appearing happier and more relaxed and others a bit “put out”. The media went a little bit crazy in this respect. They were saying that dogs were faring better and that cats were hating having their owners at home.”

“Actually, only in a few cases, cats were demonstrating that they were put out by their owners being home more often,” Oliva says. “For example, there were cats that used to sit on the couch or on the bed that were suddenly snubbing their owners, or giving them a cold shoulder, or they didn’t want to be in the room with them anymore. That was probably devastating for some of the owners. But that was only a minority of cats.”

Pets and their people after the lockdowns

When the lockdown periods were finally over, Oliva and her student Rachel Rou Qian Lau asked pet owners again how they and their animals were coping. 101 dog owners and 107 cat owners filled in the online questionnaire. Their results show that many people had become used to staying at home, and that they were still worried about going out during the pandemic. So, the situation for many pets hadn’t actually changed.

But some of the cat owners who began to leave the house again mentioned that their cats weren’t too happy with the new situation. “We found again that there was this change in the cats, that they would be unhappy their owners were not home as often,” Jessica says.

“I think that really just means that cats are creatures of habit, more so maybe than dogs. They get upset by a change in their routine rather than the actual presence or absence of the owner.”

Of course, not only single people have pets. “It would be interesting and important to look at the pet relationships in multi-person households as well,” Jessica says. “But I just couldn't resist looking at this experience in people living alone, while their other interactions during this time were pretty much non-existent.”

Teaching and research after the pandemic

Now that the lockdowns are over, and people and their pets have adjusted spending more time outside, Jessica is also happy to leave this research chapter behind her. She is back in class and teaches “Exploring Psychology” (“From Brain to Practice” and “From Perception to Reality”) at JCU.

“I absolutely love working face-to-face with students. It's just something different about that than working online,” Jessica says. “The university experience is more than getting the content across. You simply can't replace the face-to-experience.”

Jessica is still interested in how humans and dogs interact, and she has now turned to what people believe they think about drug detector dogs, in cooperation with Mia L. Cobb from the Working Dog Alliance in Australia. After all, people and their pets have a long history of bonding with each other, and there is still so much to be discovered.

Featured researcher

Dr Jessica Oliva

Senior Lecturer, Psychology

As a psychology academic specialising in human-animal interactions, Dr Jessica Oliva’s research focuses on the role animal play in the lives of humans, and the development of human attitudes and empathy towards animals.

After completing her post-doctoral fellowship at the Institute of Research in Semi-chemistry and Applied Ethology (IRSEA) in France, where she investigated, among others, the efficacy of Dog Appeasing Pheromone (DAP) versus oxytocin. Jessica researched human-dog attachment in Seeing Eye Dog puppy raiser populations through collaborations with Vision Australia. Dr Oliva's research has been featured in numerous print media articles, and presented on national and international radio programs and the national television news. She has been an invited reviewer for several Journal articles, as well as an Editor for a special Frontiers in Psychology research issue on ‘Oxytocin and Social Behaviour in Dogs and Other (Self-) Domesticated Species’. Jessica has also supervised over 20 student research projects.