Written By

Bianca de Loryn

College/Division

College of Science and Engineering

Publish Date

1 March 2022

Related Study Areas

Coral reef fisheries feed millions of people

Millions of people rely on fish and seafood from coral reefs. Some fishermen don’t care about illegally taking fish or other animals from no-take zones in marine parks. How hard can it be to change their minds? That is what Dr Brock Bergseth is trying to find out.

Coral reef fisheries support millions of people worldwide, often in developing countries where people are living near or below the poverty line. But the animals that rely on coral reefs are under threat. They are not only threatened by pollution and climate change but also by poaching. “Poaching is an immediate, and incredibly tenacious problem that is one of the largest obstacles towards sustainable fisheries worldwide,” says Dr Brock Bergseth of JCU’s ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies.

But what is poaching? Poaching is when people illegally take wildlife or fish in areas where wildlife is protected, for example in marine reserves or in marine protected areas. It is easy to declare a certain area as protected, but it can be hard to convince the people living in this area to respect the ‘no-take zones’ where absolutely no fish or animals can be taken.

Poaching in ‘paper parks’

“Many marine parks lack the resources and capacity — whether financial or human — to properly enforce the rules and manage stakeholders such as fishers,” Brock says. “We call these ‘paper parks’: they exist on paper, but not in reality.”

These ‘paper parks’ often exist in developing countries where fish populations are already overexploited, and the protection is minimal where it would be needed most. Since there is no money or no staff available for policing these areas, the problem has to be approached in a different way, in a way that takes money out the equation .

This is where social norms can help — social norms affect our behaviour in everyday life, even if we don’t notice them. “Whether it’s the side of the stairs we walk on, the way we behave when we’re in an elevator, or the type of clothes we wear to fit in, all of these are influenced by norms,” Brock says. He adds that “research suggests we can use the power of these norms to increase compliance with conservation regulations as well.”

When poaching feeds a family

Sometimes the situation gets even more complicated. For example, when it comes to people needing to feed their families. “First and foremost, conservation practices need to be both just and fair for the fishers that are affected,” Brock says. “In this case, it may not be just or ethical to force compliance from fishers who are struggling to survive if they don’t have any other alternative livelihood options.”

Finding the best solutions with the local community

There is no one-size-fits-all solution. There is still a lot to be learned before one can decide what is best for a certain marine park. Brock’s research focuses on how social influence, such as norms, can be used to convince people not to poach in marine protected areas in Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and also in Australia.

“These three countries have a range of fisheries — recreational, commercial, and subsistence — and cultural contexts, which will allow me to compare the success of norms in these different settings.”

For this research, Brock will be working closely with local conservation practitioners and organisations. “We need to understand the local social and personal norms about poaching, and reporting illegal fishing,” he says. “We’ll use a mix of methods to understand these, such as community consultations, workshops, and pilot surveys.”

Getting local leaders on board – but also the children

When the local norm is that poaching is not something to be worried about, this can be changed and replaced by norms that encourage people to follow the rules. “Part of our strategy to instil or reinforce these pro-conservation norms will rely on identifying and working with high-status leaders in local communities,” Brock says. “Whether they are community leaders and elders, religious leaders, or fishing organisation leaders, as often times some people may be more than one.”

Children can also be a part of the solution, if they understand why coral reef conservation is important. “Oftentimes, children bring these values and perspectives back home to their parents, and through their discussions, apply considerable levels of social pressure,” Brock says. “Educating and empowering children is likely a very powerful and underappreciated way to instil long lasting cultural change.”

Find people that are committed to the cause

Research has shown that you do not have to convince everybody. It already helps if one in four people support a certain norm — such as ‘poaching is evil’. “If they are vocally committed to maintaining and bolstering this norm, social pressure and people’s innate desire to fit in should do the rest of the work for us, and win over the rest of the population,” Brock says. “Human beings are social creatures — I’ll be looking to make use of this to deliver positive conservation outcomes.”

Success stories: How to stop poaching

Luckily, there are already success stories that Brock can draw on for his research. “Gaining the participation and support of local fishers is often a critical first step, especially if fishers see themselves as stewards of their environment,” Brock says.

An example is Apo Island Marine Reserve in the Philippines. “Fishers were involved in all steps of the marine reserve’s development and ongoing management and enforcement practices,” he says. “They have skin in the game, the reserve is located on their doorstep. They regularly patrol and enforce the rules, and are incredibly proud of the prestige of their marine reserve.”

Fairness and transparency can stop poaching

Another option is to explain why marine parks need protection. “Compliance is likely to be much higher if fishers think punishment is likely, and if rules and managers are seen as legitimate, transparent, and fair,” Brock says.

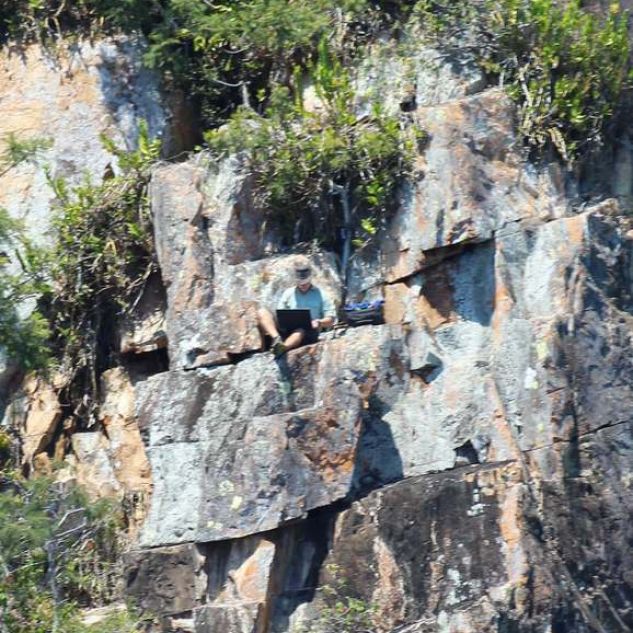

Looking into the future of his research project, Brock says it will be quite the adventure. “I’ll be working hand in hand with conservation managers to ensure that the research is of practical use, and tailored to local contexts and needs,” he says.

Science at JCU

Brock won the Discovery Early Career Researcher Award 2021 for his current research project on poaching in marine reserves in Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and Australia.

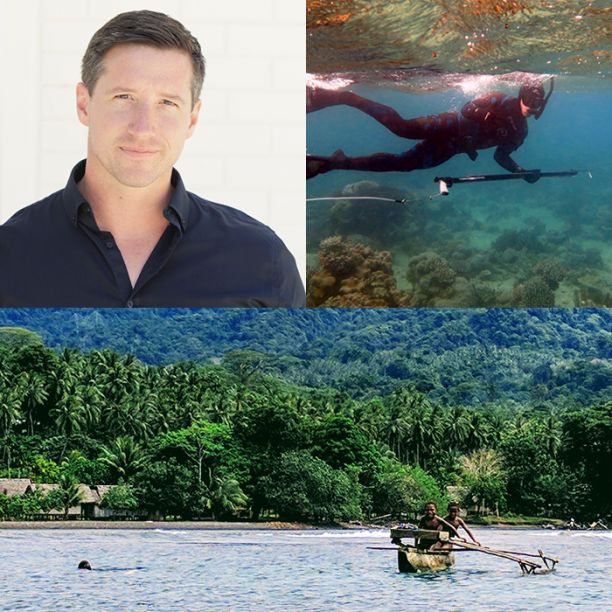

Featured researcher

Dr Brock Bergseth

Research Fellow - People and Ecosystems ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies

Brock has always been captivated by both the natural world and human behaviour. Growing up in rural Minnesota fostered a deep appreciation and passion for the wilderness, outdoors adventures, and environmental stewardship. This grounding shapes his approach to research, which seeks to understand and influence human behaviour to bolster the effectiveness of conservation programs. As an interdisciplinary conservation scientist, Brock combines disciplines such as ecology, social psychology, criminology, and behavioural economics to understand the nature and implications of human interactions with coral reef ecosystems.

A central tenet of his approach is working with key end-user groups to develop and deliver research programs that address key conservation priorities, such as reducing illegal fishing and poaching. Brock’s professional experience is diverse, and spans a range of roles working in academic, industrial, and philanthropic sectors.