Written By

Bianca de Loryn

College/Division

College of Arts, Society and Education

Publish Date

13 November 2023

Related Study Areas

The lost year

When PhD Candidate in History and Creative Writing, Bethany Keats, decided to investigate a mystery about the year her late grandmother went “missing”, she found that the family story doesn’t always match the historical record.

This article discusses sensitive content and references issues that readers may find confronting. If this article raises issues for you or anyone you know, please contact 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au.

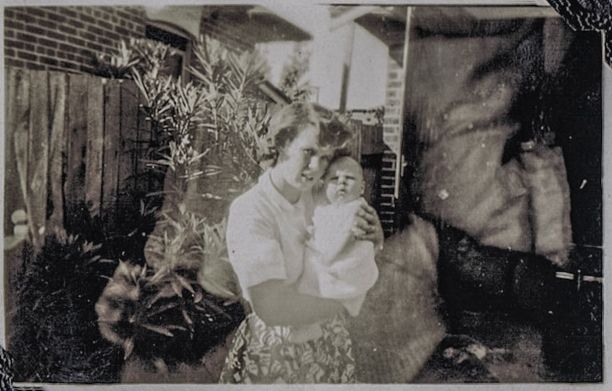

“There’s a family story I heard when I was a teenager, from my grandfather’s sister, that my grandmother left the kids with my grandfather and his family in the late 1950s, ran away for a year, and then came back, grabbed the kids and left forever,” Bethany says. “I’ve always wondered what happened to her during that ‘lost year.’ Where did she go?”

Bethany decided to dig deeper into this family mystery as part of a PhD in History and Creative Writing. She knew from the very start that probably no one will ever find out what actually happened during that time. So, she decided to draw on historical research and creative writing methods to turn her findings into a historical novel.

“Primary evidence is of course important. But you need to acknowledge its limits,” Bethany says. For her, this means that whenever the series of events are unclear, she aims to imagine what was likely to have happened.

Plausibility in historical fiction

“I am especially interested in looking at plausibility in historical fiction as part of the creative narrative,” Bethany says. “I can use creativity as a way to speculate the answer to the mystery — but it needs to be plausible.

“I want my dad and his siblings to read the novel and say ‘yes, this could be what happened’. I want my family and those who knew her to recognise her in the story,” Bethany says. This is why there are also limits to Bethany’s imagining of her grandmother’s life in the 1950s. “For instance, I can't say that she ran away to join the circus because that is absolutely not plausible.”

The truth is not always easy to digest

One of Bethany’s relatives suggested that her grandmother may have gone back to England for the year, which Bethany says seemed plausible. However, archival research was able to provide clear answers to this question. “I looked up the immigration records and I couldn't find hers,” Bethany says. “So, now I know she probably didn't leave the country.”

Bethany says that when researching family history it is important to look beyond the simple details of names, dates and occupations. “Think closely about the people and the context in which they lived. It can be difficult, it can be painful, and you can uncover things that you might not want to uncover,” she says. “But it will give a richer understanding of the past and where your family came from.”

Applying for divorce in the 1950s

When going back in time, it’s also important to understand that social attitudes were different to how they are now. For example, in the 1950s, less than ten per cent of marriages ended in divorce, Bethany says.

“My grandmother was a survivor of domestic and family violence. She successfully obtained a divorce from my grandfather for domestic violence in an era when it was very difficult to do so,” Bethany says.

“At the time, less than four per cent of divorces in New South Wales were for domestic violence. In some states it wasn't even grounds for divorce.”

Bethany says that this made her think about the environment that her grandmother was living in, and that the late 1950s must have been a difficult time for a mother of three away from the support of her extended family.

Exploring the Australian Gothic genre

This knowledge about her grandmother motivated Bethany to write the novel firmly within the Australian Gothic genre. “The Australian Gothic contains elements of unease and that unsettling feeling about where you are. The unease can come from the environment that you're living in, whether it’s the great outdoors or local suburbia,” Bethany says.

“Australian Gothic, as well as traditional Gothic literature, also explores gender relations and the status of women in patriarchal society. What my grandmother was experiencing, and that anxiety of trying to leave my grandfather, felt like it could be written about using the Australian Gothic. So, I decided to incorporate that in my novel.”

Bethany is currently working on her novel and planning to have a first draft finished by the end of the year. Given that she is a part-time student, the final draft of the book is still some time away.

Tips for future PhD students

Bethany says that one of the things that were important to her when deciding to embark on the PhD journey was that her advisors, Adjunct Associate Professor Cheryl Taylor, Dr Lyndon Megarrity, and Professor Stephen Naylor, supported her to flexibly complete a PhD as a part-time student.

“Part-time PhD study is extremely challenging,” she said. “You are constantly juggling your time and energy, but it is possible, and I am glad that I am working on this project now.”